St. Louis Rams Shallow Cross Concepts

The vertical passing game is well documented and very important (in fact they run the 3-vertical I link to in the previous post), but the shallow cross has been a great tool for them to hit passes underneath the fast dropping linebackers and to get good matchups with speed receivers getting rubs and running away from man to man for big play potential.

The Rams integrate the shallow cross into four main concepts: drive/cross-in combo (same side), hi-lo (shallow/in opposite sides), mesh, and the choice.

Running the Route

The route is designed to be run at a depth of 5-6 yards. It is mandatory that it at least crosses the center, and often can be caught on the opposite side of the field (in fact many pro-teams use the shallow as a way to attack and control the opposite flats). Here is the route shown vs. both man and zone and some coaching points:

1. First step is directly upfield. Vs. press man stutter step and get inside position.

2. Rub underneath any playside receivers inside of you.

3. Initially aim for the heels of the defensive linemen

4. Cross center. Aim for 5-6 yards on opposite hash.

5. Read man or zone (described below)

6. Vs. zone settle in window facing QB past the center-line (usually past the tackle). Get shoulders square to QB, catch the ball and get directly upfield.

7. Vs. man staircase the route (shown above, push upfield a step or two) and then break flat across again and keep running. No staircasing when running mesh.

Reading man or zone: After your initial step, eye the defenders on the opposite side of the centerline. Two questions: who are they looking at? and what does their drop look like?

If they are looking at the receivers releasing to their side and turning their shoulders to run with those receivers, it is probably man (on mesh look if they are following the opposite receiver).

If they are dropping back square and looking at either the QB or at you, it is probably zone. Expect to settle. Even if it is zone and there is nothing but open space, keep running; we'd rather hit a moving receiver than a stationary one.

Now, onto the concepts themselves.

Drive/Shallow-in

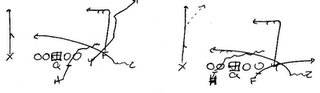

The first is the "drive" concept, as taught in the west coast offense. You can find a great article on the classic form of the play common to west coast offense teams here. Here is a diagram below:

This is the most versatile of all the shallow-cross routes, and my personal favorite. The in route is run at 14-15 yards (can shorten to 10-12 for H.S.) and the corner is a 14 yard route (can also be shortened to 10-12).

The Rams typically use two different reads on the play, depending if it is man or zone. Against man the read is shallow->in->corner (RB dump off). Against zone it is a hi-lo: corner (or wheel), in, to shallow.

The shallow and sometimes a quick flat are good options built in against blitz, and the play can be run from many formations, including the bunch.

Below are some variants. On the right, is incorporating an angle route into the play, and it always gets read inside to out. On the left, the play is run from a balanced one-back set, and the backside can have almost any two-man combination used. Below the smash is shown, but it could be curl/flat, out/seam, post-curl, or any other combination. Typically a pre-snap or post-snap determination can be made based on man/zone or whether the coverage rotates strong.

Hi/Lo

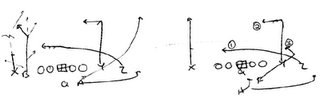

The hi/lo shallow concepts is similar to how Texas Tech/Mike Leach and the other Airraid gurus run their shallow series. For more info, try the link. Below is what the Rams do.

The in route is at 15 yards as is the post route. Both can be shortened to 10-12 for lower levels. The frontside corner is run at 15 and is only thrown vs. certain man looks.

The base read is in->shallow->RB dump-off. (As a footnote, Texas Tech reads it always shallow->in->RB. I think this is probably the better read for lower levels QBs, since it ensures they will get the ball off quickly and get a sure completion, only throwing the route over the middle when the defenders maul/jump the shallow.)

Also, versus quarters coverage the Rams like to look through the In to the Post route. The idea is that if the safety jumps the In they can hit the post up top behind him. Typically the weak safety (to in/post side) is watched on the early part of the drop, and if he comes up for whatever reason (probably to cover when a blitz is on!) the post becomes the #1 read.

The pass on the right is read the exact same, just some of the responsibilities are switched.

Mesh

The mesh route has extensive literature and discussion on it and the intricasies of the meshing receivers can be found elsewhere. The basic gist is that two receivers cross over the middle getting a rub, which is very effective versus man. Sometimes it also can be a horizontal stretch against zones with four underneath men. Martz has adjusted the play so instead of a frontside corner hi/lo read or even a post to take the top off like Norm Chow likes, he has the Z receiver running a curl at 12 yards over the center. What happens then is it floods the underneath zones with four defenders to cover five receivers, just like on all-curl. So it is a very effective man and zone play. Also, almost always at least one of the two receivers threatening the flats will run a wheel route, giving a deep option.

The QB will get a pre-snap read for the wheel route, basically checking to see if a LB has him in man and/or if the deep defender to that side might squeeze down with no immediate deep threat. The read is then right to left, X-Z-Y, or shallow, in, shallow. Again, as before, the shallows will look to settle vs. zone but they need to get a little wider here. Also, as explained elsewhere for the mesh the Y sets the top of the mesh at 6 yards and X comes underneath at 5. It is best if they can cross going full speed, but must navigate the LBs and undercoverage (and the ref!). If all is covered vs. zone the ball can be dropped off to the flat to the RB or tight end/H-back.

Choice

The Rams call the play with numbers and will tag either the post/middle read or the shallow so I'm not sure what they call it, but the play is adapted from the old run and shoot choice route. The choice route has been successful for teams for years, and the Rams are only happy to incorporate its concepts.

However, while the choice is typically read from the single receiver side over, the Rams read it opposite, with the single receiver side the late read and the middle-read the primary. The play is really intended as a spring to a slot receiver or RB in the seam with the ability to read on the fly.

They change the reads up for the post/seam pattern here run by F and H, but essentially it is similar to the middle read on the 3-vertical play, where he reads MOFO or MOFC and looks to attack the deep middle against open coverage and break flat across underneath a deep middle safety. The Rams also give him the option to break it off against blitzes and, in the case of getting H out in the second diagram, versus "wide" coverage (i.e. a LB squatting outside waiting for him to go to the flat) he can stick it at the LOS or just beyond and run an angle back inside (it helps to have Marshall Faulk!).

The read is post-read->shallow->comeback/flat read. So if they squeeze the post-read the shallow is next and then the QB works the comeback and the flat off a hi/lo read. In the second diagram the seam just clears out or breaks off his route if there is a blitz.

I suggest against having hot reads and sight adjustments to both sides combined with a multi-direction read route unless you are the St. Louis Rams. It is still an excellent play if you keep at least 6 in to block and let the shallow be the hot read, or you can even run it as a 7 man protection if you take away the backside comeback route.

Conclusion

That's a brief overview of the various ways they go about it and the reads. A HS team needs one, maybe two ways of doing this. Lots of teams have been successful using some of these. Florida State won a championship and Charlie Ward a Heisman trophy running the drive version, where if the D dropped off and covered the shallow, swing, and curl, he ran a draw. All of these are high percentage throws. Remember: speed in space! It's a motto that scores points and wins games.

Corner Routes/3-Verticals

Norm Chow on Playcalling

We are going to try to take advantage of what the other team is doing on defense. During the course of a game, with the sophistication of defenses, coverages are disguised and the use of zone blitzes and fire blitzes become very hard to beat. We’d be lying if we said we sat up in the box and knew what coverages were being run. What we try to do is take a portion of the football field, the weak flat for example, and we will attack that until we can figure out what the defense’s intentions are. Then we try to attack the coverage that we see. It is very difficult to cover the whole field. We are not going to try to fool anybody. We are going to take little portions of the field and try to attack them until the defense declares what it intends to do.

That is wisdom right there. First, to admit that you can't stand back and make magical judgments about what the defense is doing or what its intentions are. Second, the proper response is to try to turn the game into something manageable--i.e. attacking these "portions" of the field with mirrored reads, flood routes, etc.

Here's another good one:

Number one, we are going to protect the quarterback. If you decide to rush seven, we will block seven. If you decide to rush 10, we will try to block 10. We are going to try to protect the quarterback. Lance and Roger spend a lot of time picking up blitzes and that is the basic tenet that we have. You may be better than we are, but schematically we will try to protect the quarterback.

How often is this forgotten! I am a spread guy, I have roots of the pro-spread, the run and shoot, and there is a fact that the defense can always bring one more than you can protect, but protection first is the proper mindset. Hot routes are not what you build your offense on and you do not declare that you are a four wide team and that this fact is immutable. You have the ability to adapt to different defensive responses and protect your kid back there who is trying to find receivers without getting his head taken off.

Airraid Info

If you want to learn more I suggest checking out the Valdosta St/Chris Hatcher tapes on the Airraid offense and routes for the Y receiver/tight end.

Schemes and articles:

Hal Mumme Clinic Notes - Shallow Cross Series

Valdosta St - Chris Hatcher - Crossing Routes

Texas Tech - 4 Verticals Package

Playbooks

Valdosta St - Spring Playbook

Chucknduck Site - Airraid (from 1999 Oklahoma Playbook)

Remember, they got much of their offense from BYU's offense from the 80s and, even today has lots of similarities with what Norm Chow did at BYU, NC State, and Southern Cal.

Norm Chow - BYU Passing Game Article - Great Article!

Chucknduck - BYU Passing game

Playbook - BYU 1995

Last, here are Norm Chow's reads for his passing plays (see the Chucknduck link for quick reference to diagrams). The reads for the Airraid are very similar, if not the same in all respects.

NORM CHOW POST SNAP READS – “60 SERIES”

“61 Y OPTION” – 5 step drop. Eye Y and throw it to him unless taken away from the outside by S/S (then hit Z), OR inside by ILB (then hit FB). Don’t throw option route vs. man until receiver makes eye contact with you. Vs. zone – can put it in seam. Vs. zone – no hitch step. Vs. man – MAY need hitch step.

“62” MESH – 5 step drop. Take a peek at F/S – if he’s up hit Z on post. Otherwise watch X-Y mesh occur – somebody will pop open – let him have ball. Vs. zone – throw to Fullback.

“63” DIG – 5 step drop and hitch (7 steps permissible). Read F/S: X = #1; Z = #2; Y OR HB = #3.

“64” OUT– 5 step drop. Key best located Safety on 1st step. Vs. 3 deep look at F/S – if he goes weak – go strong (Z = #1 to FB = #2 off S/S); if he goes straight back or strong – go weak (X = #1 to HB = #2 off Will LB). Vs. 5 under man – Y is your only choice. Vs. 5 under zone – X & Z will fade.

“65” FLOOD ("Y-Sail") – 5 step drop and hitch. Read the S/S. Peek at Z #1; Y = #2; FB = #3. As you eyeball #2 & see color (F/S flash to Y) go to post to X. Vs. 2 deep zone go to Z = #1 to Y = #2 off S/S.

“66” ALL CURL– 5 step drop and hitch. On your first step read Mike LB (MLB or first LB inside Will in 3-4). If Mike goes straight back or strong – go weak (X = #1; HB = #2). If Mike goes weak – go strong (Y = #1; Z = #2; FB = #3). This is an inside-out progression. NOT GOOD vs. 2 deep 5 under.

“67” CORNER/POST/CORNER ("Shakes") – 5 step drop and hitch. Read receiver (WR) rather than defender (Corner). Vs. 2 deep go from Y = #1 to Z = #2. Vs. 3 deep read same as “64” pass (Will LB) for X = #1 or HB = #2. Equally good vs Cover 2 regardless if man OR zone under.

“68 SMASH” SMASH– 5 step drop and hitch. Vs. 2 deep look HB = #1; FB = #2 (shoot); Z = #3. Vs. 3 deep – stretch long to short to either side. Vs. man – go to WR’s on “returns”.

“69 Y-CROSS/H-Option – 5 step drop - hitch up only if you need to. Eye HB: HB = #1; Y = #2. QB & receiver MUST make eye contact vs. man. Vs. zone – receiver finds seam (takes it a little wider vs. 5 under). Only time you go to Y is if Will LB and Mike LB squeeze HB. If Will comes & F/S moves over on HB – HB is “HOT” and will turn flat quick and run away from F/S. Otherwise HB runs at his man to reinforce his position before making his break.

That should give plenty of insight into the Airraid! If you want to learn more than this, contact Texas Tech and/or Valdosta St. Both are quite generous with their time (I think Leach even has a session for HS coaches in the sprin). The best (and some might say only) way to learn an offense is to visit and watch them put it in.

Additional materials would be the Valdosta videos, and actually Norm Chow has a great video floating around about his offense, from back in the BYU days.

Mike Leach Goes Deep

The author is Michael Lewis, who wrote Moneyball (one of the best sports books around), and he gets a lot more detail than the typical bio. Leach certainly comes across as an odd character--particularly for a football coach--but it's insightful. There are also some funny comments, for example how Tech's QB Cody Hodges was shortlisted for the Maxwell Award before the season, despite not having actually started a game! Here are a couple interesting excerpts. The first quote sums up the article pretty decently:

Leach remains on the outside; like all innovators in sports, he finds himself in an uncertain social position. He has committed a faux pas: he has suggested by his methods that there is more going on out there on the (unlevel) field of play than his competitors realize, which reflects badly on them. He steals some glory from the guy who is born with advantages and uses them to become a champion. Gary O'Hagan, Leach's agent, says that he hears a great deal more from other coaches about Mike Leach than about any of his other clients. "He makes them nervous," O'Hagan says. "They don't like coaching against him; they'd rather coach against another version of themselves. It's not that they don't like him. But privately they haven't accepted him. You know how you can tell? Because when you're talking to them Monday morning, and you say, Did you see the play Leach ran on third and 26, they dismiss it immediately. Dismissive is the word. They dismiss him out of hand. And you know why? Because he's not doing things because that's the way they've always been done. It's like he's been given this chessboard, and all the pieces but none of the rules, and he's trying to figure out where all the chess pieces should go. From scratch!"

...

Either the market for quarterbacks was screwy - that is, the schools with the recruiting edge, and N.F.L. scouts, were missing big talent - or (much more likely, in Schwartz's view) Leach was finding new and better ways to extract value from his players. "They weren't scoring all these touchdowns because they had the best players," Schwartz told me recently. "They were doing it because they were smarter. Leach had found a way to make it work."

...

Wherever Mike Leach walks onto a football field, a question naturally follows. Vincent Meeks, who plays safety, puts it this way: "How does a coach who never played a down of football have the best offense in the game?" Leach actually rode the bench through his junior year in high school in Cody, Wyo. But that was it for his playing career. When he left Cody for Brigham Young University, Leach planned to become a lawyer. From B.Y.U. he went straight to Pepperdine law school, where he graduated, at the age of 25, in the top third of his class. That's when he posed the question that has sunk many a legal career: "Why do I want to be a lawyer?" One day he announced to his wife, Sharon - soon to be pregnant with their second child - that what he really wanted to be was a college football coach. ("Yeah, her side of the family flipped.") To Leach, coaching football requires the same talent that he was going to waste on the law: the talent for making arguments. He wanted to make his arguments in the form of offensive plays.

...

Leach made his way to the sideline and from his back pocket pulled a crumpled piece of paper with the notations for dozens of plays typed on it, along with a red pen. When a play doesn't work, he puts an X next to it. When a play works well, he draws a circle beside it - "to remind myself to run it again." But at the start of a game, he's unsure what's going to work. So one goal is to throw as many different things at a defense as he can, to see what it finds most disturbing. Another goal is to create as much confusion as possible for the defense while keeping things as simple as possible for the offense.

What a defense sees, when it lines up against Texas Tech, is endless variety, caused, first, by the sheer number of people racing around trying to catch a pass and then compounded by the many different routes they run. A typical football offense has three serious pass-catching threats; Texas Tech's offense has five, and it would employ more if that wasn't against the rules. Leach looks at the conventional offense - with its stocky fullback and bulky tight end seldom touching the football, used more often as blockers - and says, "You've got two positions that basically aren't doing anything." He regards receivers as raffle tickets: the more of them you have, the more likely one will hit big. Some go wide, some go deep, some come across the middle. All are fast. (When Leach recruits high-school players, he is forced to compromise on most talents, but he insists on speed.) All have been conditioned to run much more than a football player normally does. A typical N.F.L. receiver in training might run 1,500 yards of sprints a day; Texas Tech receivers run 2,500 yards. To prepare his receivers' ankles and knees for the unusual punishment of his nonstop-running offense, Leach has installed a 40-yard-long sand pit on his practice field; slogging through the sand, he says, strengthens the receivers' joints. And when they finish sprinting, they move to Leach's tennis-ball bazookas. A year of catching tiny fuzzy balls fired at their chests at 60 m.p.h. has turned many young men who got to Texas Tech with hands of stone into glue-fingered receivers.

...

"There's two ways to make it more complex for the defense," Leach says. "One is to have a whole bunch of different plays, but that's no good because then the offense experiences as much complexity as the defense. Another is a small number of plays and run it out of lots of different formations." Leach prefers new formations. "That way, you don't have to teach a guy a new thing to do," he says. "You just have to teach him new places to stand."

...

The Texas Tech offense is not just an offense; it's a mood: optimism. It is designed to maximize the possibility of something good happening rather than to minimize the possibility of something bad happening. But then something bad happened. ("It always does," Leach says.) On its third series, the Tech center cut his hand and began bleeding profusely; instead of telling anyone, or wiping it off, he snapped a blood-drenched ball that slithered out of Hodges's hand as he prepared to throw, and the huge loss of yards killed the drive.

"There's no such thing as a perfect game in football," Leach says. "I don't even think there's such a thing as the perfect play. You have 11 guys between the ages of 18 and 22 trying to do something violent and fast together, usually in pain. Someone is going to blow an assignment or do something that's not quite right."

This is one of my favorites:

"Thinking man's football" is a bit like "classy stripper": if the adjective modifies the noun too energetically, it undermines the nature of the thing. "Football's the most violent sport," Leach says. "And because of that, the most intense and emotional." Truth is, he loves the violence. ("Aw, yeah, the violence is awesome. That's the best part.") Back in the early 1980's, when he was a student at B.Y.U., he spotted a poster for a seminar, "Violence in American Sports." It was given by a visiting professor who bemoaned the influence of football on the American mind. To dramatize the point, the professor played a video of especially shocking blows delivered in college and pro football. "It had all the great hits in football you remembered and wanted to see again," Leach recalls. "Word got around campus that this guy had this great tape, and the place was jammed. Everybody was cheering the hits. I went twice."

Reading the "square" to determine coverage

POST-SNAP READS (“READING THE SQUARE”):

The most important area for determining secondary coverages is the middle of the field about 15 to 25 yards deep and about 2 yards inside of each hash. We call this area the “square”.

We normally read the “square” in our drop back passing game. Reading the “square” becomes necessary when it is impossible to determine what the coverage they are in before the snap or to make sure of secondary coverage after the snap.

In reading the “square” the QB simply looks down the middle of the field. He should not focus on either Safety but see them both in his peripheral vision.

A) If neither Safety shows up in the “square”, and both are deep, it will indicate a form of Cover 2. A quick check of Corner alignment and play will indicate whether it is a 2/Man or 2/Zone. If neither Safety shows up in the “square” and both are shallow, it will indicate a Cover 0 (blitz look).

B) If the Strong Safety shows up in the “square”, this will indicate a Cover 3 rolled weak or possibly a Cover 1.

C) If the Weak Safety shows up in the “square”, this will indicate a strong side coverage. It could be a Cover 3 or a Cover 1. If the coverage is Cover 3, it could be a Cover 3/Sky (Safety), or a Cover 3/Cloud (Corner), depending on who has the short zone.

NOTE: When either of the Safeties shows up in the “square”, the best percentage area to throw the ball in is the side that he came from! If NEITHER of the Safeties show up in the “square” – throwing the ball into the “square” is a high percentage throw.

Should you be worried about avian flu?

The world in general and the United States in particular are unprepared for a flu pandemic. Although the current strain of avian flu was discovered eight years ago, vaccine development and production are just beginning, along with stockpiling of Tamiflu. Apparently there is at present only enough vaccine for 1 percent of the U.S. population. Roche has only a limited capacity for producing Tamiflu and, as mentioned, is reluctant to license other pharmaceutical firms to produce the vaccine. The President recently announced a $7.1 billion program for improving the nation's defenses against flu pandemics, but it will take years for the program to yield substantial protection.

So we are seeing basically a repetition of the planning failures that resulted in the Hurricane Katrina debacle. The history of flu pandemics should have indicated the necessity for measures to assure an adequate response to any new pandemic, but until an unprecedented number of birds had been infected and human beings were dying from the disease, very little was done.

The causes are the familiar ones. People, including policymakers, have grave difficulty taking measures to respond to risks of small or unknown probability. This is partly because there are so many such risks that it is difficult to assess them all, and the lack of solid probability estimates makes prioritizing the risks inescapably arbitrary, and it is partly because politicians have truncated horizons that lead them to focus on immediate threats to the neglect of more remote ones that may be more serious. ("Remote" in the sense that, if the annual probability of some untoward event is low, the event, though it could occur at any time, would be unlikely to occur before most current senior officials leave office.) But by the time a threat becomes immediate, it may be too late to take effective response measures.

There is also a psychological or cognitive impediment--an "imagination cost"--to thinking seriously about risks with which there is little recent experience. Wishful thinking plays a role too. There is the inverse Chicken Little problem: the illogical reaction that because the swine-flu pandemic never materialized, no flu pandemic will ever materialize. Another example of wishful thinking is the argument that most people afflicted by the Spanish flu in the 1918-1919 pandemic died not of flu, but of bacterial diseases such as pneumonia that the flu made them more vulnerable to. But, first, is is far from clear that "most" died of such diseases, and, second, the current strain of avian flu appears to be more lethal than the Spanish flu. Only about 1 percent of Spanish flu victims died, whereas 50 percent of known human victims of the current avian flu have died. That percentage is probably an overestimate because many of the milder cases may not have been reported or may have been misdiagnosed; but it is unlikely that the true fatality rate is only one-fiftieth of the current reported rate. It is estimated that even a "medium-level" flu pandemic could cause up to 200,000 U.S. deaths and a purely economic impact (that is, ignoring the nonpecuniary cost of death and illness) of more than $150 billion.

Zone Blocking

There is a common misconception that on zone plays - everybody "zones". Zone plays start out as simple base man on man blocking, and if you are uncovered - you zone with your playside teammate. In a 2 TE Oneback set - it is not unusual for only TWO of the 7 O-Linemen to be zone blocking (say if everybody is covered except for the Center, as example).

When an uncovered man zones - he zones playside. A covered man zones with his backside teammate. Think of it as an inside/out double team.

Makes a lot more sense. Also for an excellent explanation, check out this article from American Footbally Monthly.

Colts Stretch Play

Their favorite run play is the stretch play, also known as the outside zone. They are also extremely effective at play action passing off the stretch action, where Peyton Manning makes those great run fakes that the announcers go crazy about. (From what I can tell their favorite routes from their play action from the stretch are post/dig, double posts, and post/corner/post combinations).

Anyway, they run their stretch a bit differently, since instead having everyone step and reach playside and getting movement that way, they run a kind of "pin and pull" scheme, which at the college level the Minnesota Golden Gophers also run with great success.

The diagrams/explanation is not directly from the Colts but it is what they do.

Onward:

The Indianapolis Colts and The "Pin and Pull" Stretch Play

Intro

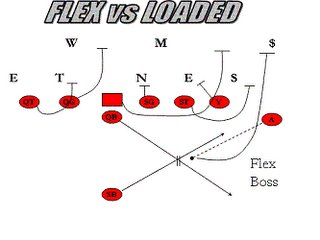

[In this terminology, the play is called "flex."]

FLEX is a strong side play.

The aiming point for the Single Back is 1 yard outside of the TE.

If the “A” is play side he is responsible for blocking the force (strong safety) defender.

If the “A” is aligned on the backside of the play he must start on an inside path and block the most dangerous pursuing defender

After the exchange the QB will set-up like he does on PISTOL protection

If the “A” is in motion prior to the snap and we want him to block the force defender on the play side we will call FLEX BOSS.

BOSS means Back On Strong Safety

Against "Under"

If the Center can reach the Nose he will make a “YOU” call to the Strong Guard telling the Strong Guard to pull and block the M(ike) linebacker.

The Strong Tackle and Tight End will “TEX”. The TE must block DOWN and not allow any penetration. The Strong Tackle needs to pull and RUN TO REACH the S(am) linebacker.

Against "Loaded"

If the Center cannot reach the Nose he will make a “ME” call to the strong guard telling him to block the Nose and the Center will pull to block the M(ike).

The Strong Guard must block DOWN and not allow the Nose to penetrate.

The Strong Tackle and the TE will “TEX," as described above.

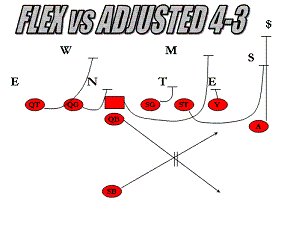

Against "Adjusted 4-3"

The Tight End is responsible for blocking the DE wherever he aligns.

The Strong Tackle is responsible for pulling and blocking the SLB’er wherever he aligns. Stay square and see the Sam linebacker during the pull.

The Center is responsible for blocking the Mike linebacker. The Quick Guard has a difficult block and must be prepared to SCRAMBLE block the Nose.

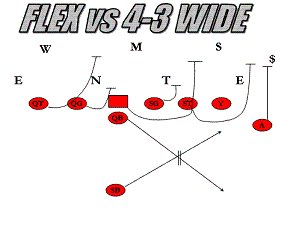

Against "4-3 Wide"

The Tight End is responsible for blocking the DE wherever he aligns. STEP-CROSS-STEP to reach the DE.

The Strong Tackle is responsible for pulling and blocking the Sam linebacker. Stay square and see the Sam linebacker during the pull - you could go around OR inside of the TE’s block.

The Center is responsible for blocking the Mike linebacker & the Quick Guard blocks the Nose.

Offense: Indianapolis Colts

Anyway, the Colts go to the line w/ three plays: run left, run right, and a pass. Peyton Manning selects among them.

They run lots of the stretch play with pullers (similar to the Minnesota Gophers, I believe) and inside zone and a called cutback with zone action. They obviously like to runs lots of play action off the stretch and it they like to throw the post/dig combo and some kind of corners on the outside with a seam/post by the slot/TE.

The Colts throw lots of hitches and lots of smashes. I believe what they do, I know other NFL teams do it, is run this as a conversion route. The outside guy always runs a hitch; the slot runs either a corner at 10-12 or a seam. Depending on his key, he looks for either MOFO/MOFC or reads the deep outside 1/3, i.e. if someone is deep outside he runs a seam, if not he will run a corner. QB reads the deep outside 1/3, and takes either a 3-step drop (hitch), or a 5-step drop (corner/smash).

Their formations are super simple, almost always a split outside WR to either side and one tight end and one RB, and they mix in either a slot or a 2nd tight end a lot.

Charlie Weis - Run and Shooter?

Anyway, though, this quote was interesting from a recent press conference:

Q. Coach, after watching Saturday, this question begs to be asked: Did your career path ever intersect with Mouse Davis?

COACH WEIS: I did visit with Mouse Davis back in South Carolina when we had the run and shoot. We talked to Mouse Davis, we talked to John Jenkins not Father John Jenkins, by the way Mouse Davis, John Jenkins, those run and shoot guys. Yes, we went from the veer to the run and shoot at South Carolina. We spent some time with all of those run and shoot guys.

Q. Was influences of that evident on Saturday?

COACH WEIS: No. What you saw Saturday [ND did a lot of 5 wide stuff and quick three step passes], first of all, run and shoot always has a back in the backfield. It's either a two by two or three by one, which trips are spread; okay, that's number one. And you always have a run element, so empty (backfield) really doesn't come into play.

If you talk about the look passes [the one step hitch] and swings that we throw in the game, that's just an evolvement from check with me(s) that we've been running over the years.

I would not have thought that Weis had been involved with "the shoot," but it isn't susprising that he is well versed in lots of football offense. While studying the Run and shoot won't give you much insight into what Weis is doing now, it's still a sophisticated offense and an understanding of the run and shoot, why it worked so well and for so long, and some of the defensive reactions and reasons why it isn't as popular anymore (though most of the diehard shooters will tell you it is simply from a lack of commitment) is as good an introduction into the passing game and modern football as you're going to get.

Further, the first time I coached on a pass-first team was with a run and shoot squad: I coached receivers, slotbacks, and defensive ends (outside linebackers) on a small squad.

The best run and shoot resources are Al Black's book, listed on the right side of the menu. The chucknduck site has diagrams of the 6 main packages vs. the relevant defenses. Tommy Browder has a website with diagrams and explanations of the tradition R&S pass protection, screen game, etc (note the midi that plays when you go to it, I think that website is or is getting close to 10 years old).

Footnote: the "go" with its "middle read route" has become, in various forms, a staple of nearly every offense, and "the switch" is still maybe one of the most explosive pass plays you can put in. Ironically, the most vivid recent memory I have of "the switch" is that in the Super Bowl that the Rams lost to the Patriots, the Rams' TD that put them ahead to set up Brady (and Weis's) game winning field goal drive was a touchdown pass to Ricky Proehl on, you guessed it, the switch.

Hal Mumme's Airraid Practice Plan

Mumme isn't having a wonderful season right now in his first season back in D-1, but it will give you pause to think that four offensive coaches from the 1997-1998 Kentucky staff are all Head Coaches: Mumme himself, Mike Leach at Texas Tech, Guy Morris at Baylor, and Coach Hatcher at Valdosta St. D-II (who is having arguably the best success of them all with a Nat'l title and currently undefeated).

Lots of coaches who email me and contact me ask about the passing game, and probably even more important than schemes are how to install it and practice it. This is one of the best explanations I've come across.

If you want to install the Airraid offense I would suggest buying the Valdosta tapes where they discuss drills and plays, using this practice plan, and contact the Texas Tech staff about visiting their spring practice and/or discussing football with them. You'll learn quite a bit. (Also, from what I understand BYU is basically running a form of the Airraid now, since their OC was from T. Tech).

HAL MUMME'S PRACTICE PLAN:

Practicing the Multiple Receiver Offense

Practice schedules and drills for the pass offense are not a lot different than those for the conventional offense but I believe a great deal of thought and preparation must be done to achieve success. In the “Air Raid” offense I have used for many years at several different levels certain nuisances have lent themselves to practicing well. I will detail these things in the article with hope it will help you.

Make Practice Consistent

The pass offense depends much on timing and chemistry between players i.e. QB and WR on route, this makes consistent practice a must. I always tried to erase doubt in the players’ minds as to what would be done in practice on any given day. I endeavored to make all the Mondays the same, all the Tuesdays the same, etc. By keeping a consistent practice schedule through each game week of the season our players could gear up mentally for the tasks to be accomplished in each segment of practice. To give an example, our individual drills were all done the same way and same segment of each day's work out. Consistent practice makes for consistent reps, which make for great reps, which makes for great play.

Practice Success

That old saying about you play like you practice is true. It was always my belief that five great reps of anything were worth more than ten mediocre reps. With this in mind, I encouraged our players to slow down their reps but to do them great. For example, if you have a QB and two WR working on the curl route don’t rush through the drill just so you can say you got ten reps. It will be a lot more productive to have the WR walk back between reps, take there time, and have five great curl routes each one perfect. Hustle is fine but is not the only ingredient. Practice successful reps even if it means fewer reps.

I never wanted to practice anything that a player could not visualize doing in a game. The successful coach should look at every drill - be it individual, group, or team type - and ask himself if this will happen in a game. If this answer is no, throw it out, it is wasted motion, which means lost time. The only resource that cannot be replaced is time. Knowing you can eliminate poor drills, look at the fruitful drills. Take each one and study how you can make them more game-like. For example, our “Air Raid” offense depended greatly on multiple sets, player groupings, and the no huddle attack. With those parameters, I decided to make all of our team offense drills more game-like by having the sideline coaches and players box painted on our practice field and requiring all our coaches and players to work and sub from where they would in the game on Saturday. This greatly enhanced the efficient use of subs and made delay of game penalties unheard of in our offense. I believe players will perform better in games if they can visualize what it will be like therefore practice game-like events.

Practice for the Unplanned Event

Every coach loves that play which happened just the way he drew it up. To be honest about it though, those are more rare than ordinary. This is particularly true in the pass offense. Practicing contingency football is very important. I would take each of our pass plays and draw up what would happen if our QB were forced to scramble to his right and then repeat the process with a scramble left. I would drill this about ten minutes per a week to make sure everyone knew where to go on the field if the QB scrambled right or left. I had landmarks for each receiver and the offense of line and running backs had specific duties. Our teams often made spectacular plays when the opponent’s defense played its best and forced our QB from the pocket. We turned our lemons into lemonade so to speak because we practiced the unplanned event.

Practice Organization is crucial to having an effective multiple receiver pass attack.

Practice Making the Big Play

Scores happen because players expect them to take place. I have certain things I want accomplished on each play from each player but the bottom line is to score. With that in mind, I made it mandatory that whomever ended up with the ball on any play had to cross the goal. In other words, our players scored on every play in practice, from individual drill right through team. I wanted all of the players to expect to score on every play. This takes some patience since the coach has to give the ball carrier time to return from the sprint to the goal. The results are worthwhile, as big plays can become habit.

Plan Success

All the practice habits described can be planned into workouts. The best time to plan workouts for the season is in the summer when the pressure is off. For this reason all of the workouts for the entire fall including bowl games or playoffs I planned in July. They were organized by day of the week and placed in a large binder to be used as needed on a daily basis. It was always amazing how few changes had to be made and how consistent our offense would become due to this planning. The most important time during the game week are the moments coaches spend with their players. By not having to devote daily time to planning practice schedules the coach has more time to spend with the players. Success can be planned well in advance.

Basic “Air Raid” Weekly Schedule-Season

Monday:

90 min. view previous game

30 min. dress-warm-up

40 min. special teams review

20 min. individual drills

30 min. walk through game plan

30 min. watch video of upcoming opponent

Tuesday:

30 min. watch video of upcoming opponent

15 min. warm-up

15 min. special teams/individual time for uninvolved

20 min. individual drills

10 min. group routes on air/OL individual drills

10 min. one on one DB-WR/inside drill

10 min. team screens

5 min. special teams

20 min. pass skel

25 min. team offense: coming off goal, open field, third and short, FGS

30 min. individual meet watch days work-out

Wednesday:

30 min. watch video of upcoming opponent

15 min. warm-up

15 min. special teams/individual time for uninvolved

20 min. individual

10 min. one on one DB-WR/inside drill

20 min. pass skel

55 min. team: goal line, red zone, third and long, open field, punt

30 min. individual meet watch days work-out

Thursday:

20 min. team meet watch previous days team video

10 min. individual meet study opponents

15 min. warm-up

35 min. special teams/individual for uninvolved

10 min. individual

10 min. team scramble drill

55 min. team game plan

10 min. sideline sub special teams

No meetings after practice

Friday:

Travel and meetings

Saturday:

Game

Sunday:

Off

New link: Coach Huey's Xs and Os

Designing a Run Game at the Youth Level

Anyway:

At the youth level I think there are three keys to designing an effective run game (arguably these are all just as important at the higher levels too), and many youth teams don't do any of them:

1. Don't ask your players to move defenders where they don't want to go. This is hard for anyone, but especially for youth players who aren't exactly doing squats and power cleans all week. Most teams seem to pick a hole and just try to run at it no matter what. One of the ideas behind zone blocking is trying to avoid this by letting the line combo block and let the running back pick his lane.

2. More blockers at the point of attack. At higher levels pulling guards and power at the POA is deterred by the defenses' overall team speed and their ability to read keys like pulling linemen. Most youth defenses are a) not that fast, and b) not that sophisticated. Therefore, I like pulling guards and tackles and getting numbers at the point of attack. The other added bonus is allowing your linemen (particularly those linemen who are only on the line because they were just over the weight limit) to move and block on the run.

3. Misdirection and faking - This is just way underutilized. Again, some faking is less effective at higher levels because of speed and their ability to read. Also, remember when you watch a college or pro game that the pass is a much bigger threat so many runs look like play action passes, many play action passes look like runs, etc. Most youth teams' passing attacks are not so sophisticated or two-dimensional. Thus, good run fakes by multiple backs, maybe even jet sweeps are just plain necessary. This is a big problem with I-offenses at the youth level (or even one back and many poorly designed two-back ones) where all runs are obvious in where they are going.

Thomas Schelling and Gameplanning vs. Playcalling

Since he won I browsed around the web a bit, and, thanks to Marginal Revolution, here is a lecture he gave on the theory of self-restraint.

I suggest reading the essay, as it touches on a variety of interesting and at times troubling issues of self-restraint and individual and public choice. It addresses the boundaries of human capacity and consequences of our abilities and limitations when making decisions.

Schelling begins his lecture:

A few years ago I saw again, after nearly fifty years, the original Moby Dick, an early talkie in black and white. Ahab, in a bunk below deck after his leg is severed by the whale, watches the ship’s blacksmith approach with a red-hot iron which, only slightly cooled by momentary immersion in a bucket of water, is to cauterize his stump. As three seamen hold him he pleads not to be burnt, begging in horror as the blacksmith throws back the blanket. And as the iron touches his body he spews out the apple that he has been chewing, in the most awful scream that at age twelve I had ever heard. Nobody doubts that the sailors who held him did what they had to do, and the blacksmith too. When the story resumes there is no sign that he regrets having been cauterized or bears any grievance toward the men who, rather than defend him against the hot iron, held him at the blacksmith’s mercy. They were not protecting him from an involuntary reflex. And he was not unaware of the medical consequences of an uncauterized wound. Until the iron touched him he knew exactly what was afoot. It was a moment of truth. He was unmistakably all there. He made his petition in clear and understandable language. They had neither personal interest nor legal obligation to subject him to torture. And they disregarded his plea. When the iron struck he went out of his mind, still able, though, to communicate with perfect fidelity that all he wanted was the pain to stop. While the iron was burning his body we might declare him to have been not fully present, but until that instant it is hard to claim that he didn’t understand better than we do what the stakes were.

Ahab and his wound dramatize a phenomenon that, usually not so terrifying, all of us have observed in others and most have observed in ourselves. It is behaving as if two selves were alternately in command. A familiar example is someone who cannot get up when the alarm goes off. [He also mentions examples like how we do not keep candy or alcohol in the house because of expectation of our own future weakness. A poignant example he uses is someone who attempts suicide.]

I don't want to misconstrue Schelling's lecture--it gets much further afield than anything here--but while reading it I was struck with the classic two-self dichotomy that every offensive coordinator in football must deal with: the gameplanner and the playcaller. (We could even probably say the 1st quarter coach vs. the 4th quarter coach, but that is a different discussion.)

Posed with similar circumstances and problems, even the exact same level of information, the in-game you and the weekday you would likely give very different answers. Bill Walsh has often talked about the advantage of scripting plays and playcalling in detached, relaxed circumstances where logic can dictate vs. the insanity of a game situation.

One of the implications is that we must take turns as Ahab and as the crew, holding each other down to see us through what our immediate self vocally rejects. Even going so far as to override us when we are at our weakest. While not as dramatic as Moby Dick or even some of Schelling's other scenarios, it is an interesting view.

Further, a gameplan can be seen as a form of contract with our football team and the other coaches that guarantees that we will stick to what has been decided collectively and with the most information possible. While it is a blueprint for attacking your opponent it is also there to guard against you suddenly becoming Hal Mumme and throwing 50 times when, as a staff, you'd decided to be a lot more like Woody Hayes that game.

The obvious caveat is that a gameplan is contingency based, much of it depends on what your opponent does. But, a well crafted gameplan can still handle these scenarios and be created in a detached setting. In Schelling's language, created by your week-day self.

Notes on Running With the Football

[In response to a question on running back Darius Walker's running style]

But I can tell you what I used to tell [Patriot's receiver] Deion Branch after I had a big research study on (Marvin) Harrison a few years ago when Deion was a second year [in New England]. I noticed that Marvin, with all of his production, any time the hits were coming, he was going down. So after I thought about it for a while. I thought, this isn't the stupidest thing in the whole world to have your best guy, when he's about ready to get crunched, go ahead and make sure that doesn't happen.... there are times to take the hit and there are times not to take the hit.

The first important point is explicitly made: If you're talking about your best guy, there is logic to letting him go down or go out and bounds and avoid the big crunching hits. While we don't want to coach pansies, you also want to have the kid for the whole season. Injuries are a bigger threat to receivers than say offensive linemen because it is more difficult for them to play through injuries due to the nature of the position.

Second, which can be gleaned since his example was Marvin Harrison, most all production, at least a receiver's, is done before contact is made. This does not limit yards after the catch, but instead tells you that the focus is on running away from defenders rather than at them, either to run them over like Earl Campbell or try to individually juke every guy out, which is idiotic.

Instead, great receivers catch the ball, get upfield immediately, and try to score by splitting defenders. What do I mean by splitting defenders? Quite simply: run inbetween them. There are circumstances when you need to take the hit to the defender (sometimes on a slant all you can do is deliver the "forearm of doom" to the safety after the catch) but, usually, you score by running directly upfield right inbetween the corner and the safety for the long TD.

It's an often missed point. If you watch Sportscenter you will see that almost every short pass that goes for a TD involves a receiver bursting through a seam rather than trying to juke guy X, run through guy Y, spin off guy Z, and then finish by jumping over guy A. Notice I ran out of letters because doing this, even if successful, takes so long that the whole defense has time to show up. It happens occaisionally, but don't make it a habit.

More considerations on developing your systems

I totally agree [with Coach Huey's response that the primary goal of an offense is to get the ball repeatedly to your best player's].

Your "system" is just a framework from which you can run your individual "offense" in a given year, based on your personnel. This is one reason that most teams like to be "multiple spread teams" or "multiple one-back," because the theory is that in a given year the focus of the O should change based on who you have. For example, if you have a powerful RB, you will probably want to line him up in single back, 6-7 yards deep--maybe even I or offset I--and run the power schemes etc and use that to set up your offense.

A great example if you are a spread offense team is when you have a running QB vs. a dropback guy. I tend to think counter-intuitively: I like to put dropback QBs under center and running QBs in the gun. Your "offense" still involves the same plays whether the QB is in the gun making fakes and running laterally on bootlegs, sprintouts, QB reads, etc, or more traditional rhythm dop passing, play action passing, etc. A fan (or hopefully an opponent!) will look at your offense though and think you are completely different.

It is easy to see that your offense is the same, the only difference is if you call your formations with "gun" in them or not. Then, in practice you emphasize one thing over another.

In the end, you have to install something you can effectively coach. Whatever you end up doing, make sure that you and your coaches believe in it and have a firm grasp of both the schemes and concepts, why and how they are used, and, most importantly, how to teach them to your kids. The biggest challenge in moving from say the wing-t or traditional I-back offense to a pass oriented or even balanced O is identifying what your players need to learn and how best to teach it in a limited amount of time, at the expense of not teaching or spending much time on other things--even things that formerly you spent a lot of time on.

Look at a Texas Tech, who is almost entirely committed to the pass. If you study them or talk to their coaches, the reason they focus so hard on the passing game at the expense of the running game is not because the players can't learn a lot of different running schemes (though this is a factor), but moreso the amount of practice time they would have to spend learning how to execute them, what kind of skills they would need, and having enough practice time to master those skills.

As a final note, the counter-argument to this is that adding a few more concepts, or a more aggressive run game or balanced attack would make the job of pass blocking for the linemen easier, or even passing itself easier. This is further argued that at some point your players don't "get any better," at a given skill, say pass blocking, than their ability would allow, so you are better off teaching something new. All coaches and systems seek to balance these two opposing forces. Further, most agree that the lower the level you coach at the fewer "things" you are going to try to do, since you must spend more time on the fundamentals and specific skills the players must learn.

What is a system?

If they systems, is what the team who hasn't won a game in 10 years does a system? Why not? They have a series of plays and communications.

I want to highlight a point: A system, in ordinary terms, is no more than a series of parts that interact and work together to form a unified whole. The word unified is helpful since it implies that things work together.

I'm not going to touch today how they work together, that's more of what the past few articles about making plays look alike and even route conversions were for. But the other side of a system is its further definition, "for serving a common purpose." A system is supposed to work!

Sometimes there is much made of "being a spread team" or "having an identity" and such. The only limitating factor for a football offense is what can be executed effectively. It has nothing to do with what you already do, what "we hang our hat on," "we're a passing team," "we're a physical team." These shouldn't even be considerations. You should just try to win games. That's it.

It begs the question: how do you win games? For now I'll just say that one possible answer is "Score more points." So--forgive me for taking the long way to get here--you need the proper "tools" (plays, schemes, formations, etc) to defeat each individual strategy the defense employs. While some plays are more useful than others, everything has a defense, so you need at least one offensive strategy for every defensive strategy (at least broadly defined) that you might face. Otherwise the rational response by the defense would be to do the same thing every down that you have no answer for.

"So you've told me that offenses only are concerned with scoring points (and other offensive goals like getting first downs at important times to control the clock) and defeat what the D is doing. What a great blog buddy!!!"

It seems simple but is important for two reasons: 1) it can help you be a better coach, and 2) it's not actually true.

First, thinking like this should get rid of many slack concerns, particularly stat watching. What was our passing percentage? What was our YPC? How many formations did we run? "Oh but it looked good coming out of your hand, it was a nice spiral, even though it was an interception." All this is meaningless if the point is to win games. We all know this, but we have to defeat these mental traps at every turn.

However, on the second point, sometimes there are other considerations. At the NFL level, it really is all about winning games. The only time things like style and all that are invoked is as an explanation for success. "Oh, the Patriots win because they play it close to the vest." "The Steelers have a great record because they are a physical team." This might be true in a sense, but it mostly comes down to them having effective strategies against their opponent, with each effective strategy being a combination of talent and scheme.

Conversely, at other levels, particularly high school or major college football, you can get more mileage out of being "exciting" than you can out of being "3 yards and a cloud of dust." I'd be lying if I didn't say that I enjoy the passing game more than more staid elements of the run game. Is it purely strategic? Fans would rather watch their team lose 42 to 63 than 28-7 (though that isn't a fair comparison since 42/63 is a better ratio).

Anyway, the overall message is do not worry about identities or styles or systems in the sense of how they look. The question is are they effective? Why is the Norm Chow system effective? Because in about 12 pass plays he has an answer for almost all defensive strategies. Where other coaches need 80, he has 12 (or 10-16 or so, give or take).

If you must concern yourself with "style" then that is fine to a point. Sometimes it is more psychological than anything. But a true "system" is simply concerned with how good the individual parts are at working together to help you win games. If you could win all your games and never throw a pass, I would suggest you do it. Same if you never ran the ball. More likely, you need a mixture of strategies, integrated in such a way to be teachable to kids aged 14-18 (or 18-22, even 10-13, etc) during limited time. It's not easy.

Routes vs. Press Man

While I agree that the mesh [two receivers shallow crossing at 6 yards, making a rub] is a great play vs man, it can take a little while to develop. I've definitely seen one or both receivers get jammed and the QB left with nowhere to go with the ball. I don't really think the Kentucky Shallow Cross Series is that inherently great versus press man. [an example play is here, more info can be found here. Both were mentioned in the discussion.]

I think shallow crosses work better versus loose man and zones where you can widen the linebackers. There aren't many rubs and the actual pass to the crosser is not always an easy throw against even a beaten defender; it's kind of is to the side and sometimes even over the defender.

[Another poster] mentioned Spurrier: I also remember watching his Coaching show once when he was at UF, and he said "if they play tight man you're eventually going to have to throw the slant route and the fade route." These are two routes that your receivers must learn to execute one-on-one. Can they beat the man over them?

Further, to help your guys vs press man the simplest thing to do is put your receiver off the ball, i.e. as a flanker. Vary who is on and who is off to give your guys better leverage. Also, simple motions can help too; tough to jam a guy who is in motion (look at Arena football, can't quite do that same thing but the principle applies).

Last, stacks, bunches, and rubs. I group them together but two receivers working together (the essence of the Kentucky mesh, but sometimes putting them to the same side is best) works great. Have them criss cross, follow release, rub, whatever works in your system.

If Purdue sees press man they will invariably go to a really simple combination: a slant by the outside guy with the slot running a fade. The slant runs his break off the hip of the guy running the fade, so they get a "rub". The receiver breaks his route pretty flat at first but then will bend it upfield after a couple steps (he doesn't want to get too far inside, it isn't an in route).

If you are going to install any play versus press man, this is the first and easiest. The QB will look for the slant first. If they manage to cover the slant then he will look for the fade route, looking to drop it over his outside shoulder. (if it is zone you can often still free up the slant in the undercoverage, or stick the fade vs a cover 2 safety, but it is best as a man play).

Remember what I quoted Spurrier saying? Slants and fades? On this play you do both and the ball gets out much quicker than the Kentucky mesh (3 steps vs 5).

Further Note on Passing Concepts

Anyway, here is more about grouping pass concepts, this time (again via Coach Mountjoy) from Gene Dahlquist:

Another GOOD perspective on "PASSING GAME CONCEPTS" is from Gene Dahlquist (fine QB Coach at U of Texas under John Macovic - who also coached the KC Chiefs, & now coaching in NFL Europe - I believe):

CONCEPTS:

#1 - "PROGRESSIONS" = Reading progressions of receivers only;

#2 - "ONE ON ONES" = FINDING the BEST one on ones thru various types of pre-snap & post-snap reads.

#3 - "ISLOATIONS" - Just isolating 1 receiver on 1 defender on a PARTICULAR route.

#4 - "OPTIONS" - Prime receiver runs an "Option" route vs a defender (with a 4 or 5 way go).

#5 - "TWO AGAINST THE SIDELINE" (Hi/Lo off flat coverage). What I call a "2 Level Vertical Stretch".

#6 - "THREE AGAINST THE SIDELINE" - what I call a "3 Level Vertical Stretch"

#7 - "WORKING THE LEVELS" - three receivers vertically in the middle of the field (also a 3 level vertical stretch, but in mid 1/3 rather than outs. 1/3).

#8 - "THREE DEEP RECEIVERS VS TWO DEEP DEFENDERS" - horizontally stretching a 2 Deep Zone defense.

#9 - "FOUR DEEP RECEIVERS VS THREE DEEP DEFENDERS" - horizontally stretching a 3 Deep Zone defense.

#10 - "TWO RECEIVERS VS ONE DEFENDER UNDERNEATH" - horizontally stretching 1 undercoverage defender in 1/2 of the field.

#11 - "THREE RECEIVERS VS TWO UNDERNEATH DEFENDERS" - horizontally stretching 2 undercoverage defenders in 1/2 of the field.

#12 - "MAN/ZONE COMBINATIONS" - set one side of pattern to handle MAN & set the other side of the pattern to attak zone.

If you check this out, & the NORM CHOW "Concepts" posted earlier (above) - it is two different (& interesting) perspectives on "PASSING GAME CONCEPTS"!

NOTE: To MY way of thinking (CONSTANTLY trying to SIMPLIFY) - I would COMBINE many of the above into FEWER Concepts:

A) HORIZONTAL STRETCH (either INS/OUT OR OUTS/IN) would encompass #'s 8, 9, 10, & 11!

B) VERTICAL STRETCH would encompass #'s 5, 6, & 7!

C) OBJECT RECEIVER READ would encompas #'s 2, 3, & 4!

I wouldn't list #1 ("progressions") as a seperate "PASSING GAME CONCEPT" - because we have "progressions" in MOST of the concepts.

FINALLY - I think that #12 ("COMBINATIONS") is a GREAT concept!

Organizing Pass Plays as "Concepts"

I want to give lots of credit to Coach Bill Mountjoy who posts on there, as he provided most of the most useful information:

...[Mike] Martz & [Joe] Gibbs are disciples of the [Don] Coryell offense.

You have Horizontal Stretches (Inside/Out, AND Outside/IN) with either 2 on 1, or 3 on 2 (USUALLY in 1/2 of the field - deep OR under).

You have Vertical Stretches with 3 on 2, or 2 on 1 (USUALLY in 1/3 of the field).

You have "Objective Receiver Concepts" (which is with ANY pass in which a specific receiver is primary - such as "OPTION ROUTES", ETC.).

You have read concepts (below) to facilitate the above: NOTE: "MOFO" = MOF OPEN; "MOFC" = MOF CLOSED).

QUARTERBACK READ SYSTEM:

KNOW THE SITUATION

PRE-SNAP LOOK THE DEFENSE – ANTICIPATE

READ ON THE DROP – ADJUST

THINK: PROTECTION/ADJUSTMENTS/PROGRESSION/TIMING/OUTLETS

BEWARE OF THE MIDDLE OF THE FIELD LOOKS – MOFO/MOFC

KNOW THE COVERAGE ELEMENTS:

ZONE 3 DEEP MOFC/2 DEEP MOFO, etc

That's a handful. Quick notes:

Think of a football field as a flat, two dimensional plane. You attack a defense "horizontally" along a line on this plane. For example, in the All-curl, you are horizontally stretching 4 underneath defenders with 5 receivers all looking back at the QB (versus 3-deep. Versus cover 2 they now have 5 underneath defenders: one for every passing lane). Technically some of these receivers are at 3-5 yards and others are at 10, but it constitutes 5 passing lanes for only 4 defenders to cover.

This is what would be a called a "short [or intermediate] in-out horizontal stretch". The QB is reading inside to out (sit route to curl to flat), on a short horizontal stretch. The key is that you have isolated those 4 underneath defenders in a game they can't win: 4 vs 5.

However, to further facilitate reading these things easily, a coach will integrate a coverage key (here the drop of the middle linebacker) where he will then isolate himself into 1/2 of the field. Then, 5 on 4 becomes the more manageable 3 on 2.

Further, a great play is the corner/3-vertical route.

First, it is an example of a "deep out-to-in vertical stretch". You want to run this versus 2-deep, so you are stretching 2 deep defenders with 3 deep receivers. The QB would then pick a side based on the safety key, and read outside in (corner to post). Again, if you can isolate the defenders at this level, it becomes the classic game they can't win: 2 covering 3.

Further, making the play effective is it is also a "hi/lo vertical stretch". In this case you hopefully, on each 1/3 half of the field, can isolate a single sideline defender (the squat-cornerback versus cover 2) who you can attack both high and low, or "hi/lo" with your corner route and your flat--both sideline routes. Essentially this is a 2 on 1.

The point here? You do not win football games and complete passes by creating "one-on-one matchups" unless you have superior talent at each position. You win them by getting a numerical advantage, where it is 5 on 4, or 2 on 1.

We prefer 2 on 1s and they are easier--simply look at the movement of one defender--but the practical problems of properly identifying that key defender and being confident no one else will get into the passing lane are not easy, so you go for 3 on 2, 4 vs 3, or 5 on 4.

This is intended for zones, but how do you attack man? I will save some of these ideas for another article, but suffice to say that many of the best coaches will:

1. Have the individual routes that attack the zone be effective versus man (corner routes, shallow crosses)

2. Integrate certain anti-man concepts within a zone stretching framework (such as the mesh or option routes)

3. Put man combinations to one side and zone combinations to the other. Many of the best NFL and College teams do this quite effectively, and it is still simple to do.

Conclusion

Many of you probably have questions about how a Quarterback actually goes about deciding who to throw to. Even if he has a 5 on 4 situation, how in the world does he quickly determine who to throw to? Coach Mountjoy provides an excellent and quick rundown below:

You can read defenders OR progressions. Examples below:

DISCUSSION OF PROGRESSION READS AND COVERAGE READS

I. PROGRESSION READS: A progression read is designed to have two or three choices of where to go with the ball. It is important to pre-read the coverage to give you an indication of the coverage, but more importantly, it’s knowing where the receivers are going to be with a progression read pattern called. This kind of read calls for throwing the ball with rhythm drops. You might get to the third receiver in the progression as soon as you hit your fifth step on the drop. So when you are stepping forward to throw, you can hit the third receiver in the progression on the same rhythm you would have if you were throwing to the first.

The limitations of progression reads are:

A) There is a tendency to stare at the receiver that is first in the progression attracting other defenders

B) It is frustrating for coaches to watch because they could see the receiver you didn’t throw to was wide open (Coaches need to know the progression of the play as well as the QB); [i.e. QB threw it to the first read who was kinda/maybe open and #3 was uncovered].

C) You will lose patience or think that because you hit the first receiver in the progression he won’t be there when the play is called again. You must have patience and not make up your mind before the ball is snapped.

REMINDERS:

1. Have a plan when you get to the Line of Scrimmage.

2. Stay with the progression.

3. Don’t stare.

4. Progression reads are thrown with rhythm drops.

II. COVERAGE READS: Reading the coverage is normally done in the NFL looking at the pictures that are taken upstairs during the series (when the QB is on the sidelines). In High School & College – the Press Box Coaches do most of the work here. The QB can pre-snap read and get an idea of what might happen. He can see rotations and drops of defenders at the snap of the ball, but may not know what the coverage was. Reading the coverage is really looking at a defender or defenders. Based on what they do you will get to the correct receiver.

THE ADVANTAGES OF THIS KIND OF A READ ARE:

1. It eliminates the struggle of the progression read trying to determine who was more wide open.

2. It eliminates the QB from making up his mind before the snap (we shouldn’t do this regardless of if we Progression Read OR Read the Coverage). Read the defenders to get you to the right receiver in Coverage Reads.

3. It keeps the QB on the same page as the Coach because they both know the read and the goal of the play called.

4. It doesn’t matter what the coverage is because when you are reading properly you will be hitting the correct receiver.

5. You will not have to stare at your receivers (it will give you natural look offs).

6. You don’t have to know what the entire coverage is (you don’t have to see the whole field). NOTE: In our reads – “Progression” AND “Coverage” – we only read ½ the field Horizontally, or 1/3 of the field Vertically.

The Shallow Cross and the Holy Trinity from Bunch

As discussed in the last article, sending all your receivers vertically is often very difficult to pattern read for zone defenders, safeties, as well as the very disruptive rovers/floaters. However, any quick look at the football landscape reveals that many, many teams successfully use lots of shallow crosses and flat routes. Given the discussion and some doodling on paper this is a surprise. These routes are almost silly: aside from being simple to jump and wall off for many defenders, they often give away what the one or two vertically releasing receivers will do.

However, my point is not that these routes are irrelevant, yet teams should be careful how they use them and it is possible that they are overused. For example, many coaches teach the passing game based on the reaction of one defender. For example, on the curl/flat combination shown below, the coach will say that if the linebacker widens with the flat, throw the curl. However, if the defense wants to, it can always double cover the curl and cover the flat one on one and take it away.

So, briefly, why do teams run these types of routes? Of first importance is who they are run against; often it is linebackers and safeties, who are weaker pass defenders. Second, the throws themselves are often easier than other throws, which can require more timing and the ability to squeeze the ball between defenders--many of these throws are simply underneath defenders.

Third, structurally, they are easy to understand and often easy to read. While this is a fear if the defense is too good, again, simplicity often favors the offense. If I send a player immediately to the flat, then I can quickly see the defense's reaction. If I send two receivers vertical it is not apparent to the QB who the D will eventually leave uncovered.

Lastly, while they (usually) are poor at threatening vertically, they can still be packaged together to create rubs, picks, and mismatches. Whether in the traditional bunch set or simply a shoot route by a running back versus a slower linebacker, we can all envision circumstances that make them effective. Therefore these routes, often better than 3 or 4 vertically releasing receivers are good at causing the defense to put itself in a numbers bind (I.E. three defenders to cover two receivers or four defenders to cover three receivers. This is what can win football games from a strategy point of view.) The point of this article is to show some of the right ways to use them and some of the proper considerations.

I'll begin with the shallow cross series as I have run it, which has a few variations and has come under a few names, including the West Coast "drive" concept, or just shallow cross in mine. It is a simple inside-out read for the QB, who reads the shallow cross, to a curl or in-breaking route, to the flat (or sometimes a wheel route). Sometimes there are backside reads as well, but for now I will just show it with a post route and a backside flat to control the outside linebacker for the crossing receiver.

In the lower left is how Purdue runs the play, which is basically the same even if the techniques are slightly different.

However, no matter how you dress it up, the play does not exist in a vacuum. In my earlier article I talked about the same plays being run from multiple formations. Yet, the D cannot be totally fooled if every time one guy comes in, another pushes vertical, and another goes to the flat. It simply becomes recognition and reaction for the defense; in other words they can pattern read you.

Quickly, I'll show a few other combinations of routes that look similar. First, the now famous mesh/snag/triangle route:

And the follow/angle combination:

Shallow, snag, and follow (which is what I call them--insert Shakespeare's famous question here) form what I call the "Holy Trinity", which are imperative for any good passing team, particularly if you plan to use the bunch packages. Intuitively, you can see the advantage to using these together, but it becomes more apparent if I draw it first as what the stems look like on each play, and then as a branch of possibilities:

Since that looks a bit messy, here is each route individually:

The defense cannot pattern read anymore, because every play is like a kind of dynamic route tree. You've achieved the same equilibrium with these short routes as you had when all your receivers vertically released.

In this case you can still get double teamed, but they will be unable to jump the underneath routes for fear that a shallow may become a whip or that a shoot route may become a wheel or an angle route.

Conclusion

All this is part of making your offense cohesive. Again, no play exists in a vacuum. You do this for the same reason that you run draw plays or that you run your play action passes off of your favorite run plays instead of plays you don't even run. They keep the defense honest and make you difficult to defend. If I have five pass plays but they all look markedly different, I become easier to defend. If I can mix in all the formations, substitutions, and then, even if the defense accurately reads run or pass and can identify the receivers, yet still can't tell if there is a whip or a shallow coming, or a corner or a curl (or a post), then I have been successful.

It doesn't really matter how you integrate it into your system, whether they are separate plays or tags or whatnot, but the important thing is to make it difficult for the D and easy to teach. For the last two diagrams I will show you how Spurrier integrates this same idea into his two favorite pass plays (which, to add to the confusion, are built off his favorite run play, the lead draw).

First, Spurrier loves the curl/corner read play, which I discussed in this article and the common dig/post pass, shown below:

Laid on top of each other, it looks like this to the defense:

He's been doing this for years. Constant three way threats all around, the threat of multiple vertical receivers, including post and corner routes, are all staples of the Old Ball Coach's offense.

Google Pt 2

Google's Stock Sale Mystery Is

Simply Solved: There Are Buyers

August 24, 2005; Page A2

(See Corrections & Amplifications item below.)

Google's decision to issue $4 billion in new stock has been greeted with surprise and stupefaction by the army of analysts who are overpaid to divine happenings within the Googleplex.

It is an impenetrable mystery, they say. The company already has nearly $3 billion in cash; why does it need more? Are the Googlers planning to build a global wireless network? Dive headlong into Internet telephony? Construct an elevator into space? And why, oh why, the strange numerology -- selling exactly 14,159,265 shares, which every educated 13-year-old recognizes as the digits to the right of the decimal point in the mathematical term pi.

Hello?

Let's try a little test. If I offer you $100,000 for your Honda Civic, how would you respond? Here are your choices:

a) "No, thank you, my checking account is already full."

b) "Maybe, but let me look around first to see if there is another car I'd like to buy."

or

c) "Here are the keys."

If you answered a) or b), you have the makings of a Google analyst.

Is Google preparing for the bubble to burst? WSJ's Alan Murray discusses the stock sale mystery.

There is no mystery here, folks. When companies think their stock is undervalued, they buy it back. The Googlers are in the opposite fix. Their stock is overvalued, so what do they do?

Sell more. Quickly. Before sanity returns to the marketplace...